If you are thinking about OKRs, start with developing Operating Practices (OPs).

The search for better goals

In the course of digitizing their business, a lot of companies are turning to OKRs (Objectives and Key Results). The reasoning being: “If it helped Google and all those startups from the Silicon Valley, it just has to be right for us too!”

And it may very well be. It is indeed a very powerful goal-setting system that can ensure focus, alignment, aspiration and accountability.

But I have also seen a lot of companies be somewhat disappointed or outright disillusioned after having introduced OKRs to their business.

And I’d like to offer an explanation for that.

The prerequisite for OKRs

While a lot of companies claim their OKR’s helped them achieve spectacular success and growth, I think that’s actually an artifact and something else is at work here.

I’m not saying that OKRs are not useful or that you don’t need them. I’m just saying that they are not the major cause for the effect that’s attributed to them. OKRs don’t miraculously create an ambitious culture of agile disruption. It’s rather the opposite: A certain culture leads to an aggressive setting of goals which can then be aligned and focused as OKRs. OKRs are absolutely fantastic but only if they’re built on top of a certain culture.

When I say culture, I am not talking about values, by the way. Values are important but mostly not operative enough. And in most companies they are too much marketing and too little actual practice to have a major impact on daily work. It’s also all too easy to commit the fallacy of believing one has a certain culture just because one has formulated one.

Shaping culture with Operating Practices

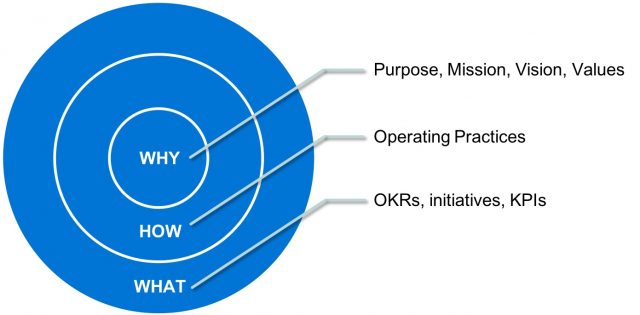

What actually drives performance must be something different than just goals. I’d like to call that Operating Practices or short OPs.

Operating practices are very simple and concrete statements on how to operate and behave.

The most famous are probably the Ten Commandments. These are ten, easy to remember rules that guarantee the functioning of a large group.

In the animal world we have the astounding examples of large anthills or swarms of birds and how they coordinate their group without anything resembling human management tools. Something seems to be encoded in each of their DNA that helps them operate in unisan without any hierarchy.

Google’s “10x thinking”

Google has a practice they call „10x thinking“. In simple terms, they think about how they can improve what they do by a factor of 10 times, rather than by 10% like others. It challenges them to think about everything they do in terms of revolutionary change rather than evolutionary change.

The “10x thinking” is not – as many believe – the result of very aspirational OKRs but was merely encoded in them. They were striving for 10x long before they implemented OKRs. It’s in the DNA of Google, not just some byproduct of having OKRs. And that’s exactly where lots of companies go wrong when introducing OKRs. They think they get the Google DNA and Google’s ambition and everyone will then miraculously shoot for the moon. But that’s nonsense. Aspirational goals without the corresponding mindset are not only useless – they can even destroy motivation.

Apple’s “There are 1000 no’s for every yes”

Turn to Apple. Steve Jobs once said “There are 1000 no’s for every yes”. Again that’s not a goal, it’s certainly not a value, but it expresses a basic operating practice: That we will say no to a lot of ideas, concepts and iteration before we actually call something “designed by Apple” and release it to the public. That’s the strive for perfection that will ultimately wow consumers. And that’s worth more than setting specific quality standards or goals in the form of a number.

Operating practices at team level

Operating practices can comprise behavior instructions that are relevant for everyone in a company. But they can also be deployed at the team level.

In a factory, for example, an operating practice could read: “We return tools immediately to the tool bin after we’re done using them”. No ifs, no buts. This is, by the way, very different from formulating a corresponding goal like “Our tools should always be available when needed”. The goal only describes a desired state or result. The operating practice ensures that the goal is actually met even in the absence of any overt goal.

Likewise a bank branch could adhere to the operating practice of “We follow a 360°-advisory approach in every one-on-one consultation with our clients”. Most banks, however, rather try to establish goals concerning 360° advisory like “80 360°-advisory discussion per relationship manager per year”. Something that should be a mindset thus is degraded to a number that one has to hit.

How to start developing your own operating practices

So how can you come up with good operating practices for your own company?

That is clearly no easy task. You can’t just copy-paste Google’s or Apple’s. Some of the best OPs are not even documented and only live in the hearts and minds of people.

A good starting point: The purpose, mission and vision of your own company or team.

WHY does the company exist in the first place? Which aspects in your company DNA are most important to you?

You can take it from there and think about actual practices:

HOW do your best people behave and operate? What do they do and what do they consciously not do?

Also think about the future: Which behavior will be crucial? What do you need more and what less?

Start with two or three practices that capture best the mindset that you’re after.

Write them down. Talk about them. Most importantly: Live them.

Make operating practices the foundation of your goal-setting:

And then, and only then, you should think about if you are ready for OKRs.

WHAT objectives do you want to achieve? How ambitious do you want to or need you to be? Which key results will help you focus and align resources? What is your team willing and able to contribute with their own OKRs? Which initiatives and KPIs will help you manage all efforts?

Sounds like a bit of work – but well worth it!

- Veröffentlicht in Inspiring Leaders, OKR, Change

OKR: Wundermittel oder alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen?

Eine kurze Einführung

Wer sie nicht schon längst eingeführt hat, sieht sich heute fast schon einer Rechtfertigung ausgesetzt: Warum haben wir noch keine OKR?

Die Rede ist von Objectives and Key Results, dem eng mit dem Silicon Valley verknüpften Zielsystem. Wann immer es um Agilität und Disruption geht, fällt auch schnell dieser Begriff. Was hat es damit auf sich? Sollte das wirklich jeder einführen? Was ist zu gewinnen? Auf was ist dabei zu achten? Ein paar erste Fragen wollen wir hier beantworten.

Zunächst einmal für alle, die es ganz kurz wollen:

Objectives and Key Results ist ein Managementsystem, um Ziele zu setzen und diese über eine ganze Organisation abzustimmen (neudeutsch: zu alignen) und zu tracken.

Das klingt zunächst nicht bahnbrechend neu. OKR sind erst mal auch nicht mehr als eine Weiterentwicklung des klassischen Management by Objectives. Sie gehen auf Andy Grove zurück, der diese in den 1980er Jahren als CEO von Intel entwickelte und damit äußert erfolgreich sein Unternehmen steuerte. John Doerr verbreitete den Ansatz und trug ihn unter anderem auch zu Google, durch die die Methode ihre heutige Popularität erreichte.

Was verspricht OKR?

- Eine Geisteshaltung groß zu denken und ambitionierte Ziele zu verfolgen („to shoot for the moon“).

- Eine Fokussierung des gesamten Unternehmens auf einige wenige wichtige Kernthemen, um diese ambitionierten Ziele auch tatsächlich zu erreichen.

- Eine rigorose Transparenz wer was beiträgt zu gemeinsamen Zielen und wo derjenige damit steht.

- Eine Kultur des gemeinsamen Wollens anstelle einer Kultur des individuellen Müssens.

Unterschiede von OKR und MbO

Dies wird bei OKR erreicht durch einige charakteristische Unterschiede zu herkömmlichen MbO-verwandten Zielvereinbarungssystemen:

| MbOs | OKRs | |

| „Was“ | „Was“ und „Wie“ | |

| Jährlich | Quartalsweise | |

| Privat | Öffentlich | |

| Top-down | Bottom-up und Sideways | |

| An Entlohnung gekoppelt | Entkoppelt von Entlohnung | |

| Konservativ | Ambitioniert |

Das wirklich Neue von OKR

- Während im klassischen MbO primär das Ziel vorgegeben und/oder vereinbart wird, wird bei OKR auch der Weg zum Ziel durch Subziele (Key Results) spezifiziert. Damit wird nicht nur klar, was erreicht werden soll, sondern auch auf welchem Weg. Indem dieser abgestimmt wird zwischen Manager und Mitarbeiter herrscht Einigkeit über Ziel und Weg.

- Die quartalsweise Durchführung hat gegenüber den jährlichen den Vorteil, dass das System weniger statisch ist und agiler auf Veränderungen reagiert werden kann. Der Nachteil soll allerdings nicht verschwiegen werden: Es führt zu einem erheblichen Zeitaufwand, Ziele jedes Quartal über das ganze Unternehmen zu erstellen und abzustimmen. Wird dieser Prozess nicht strikt und diszipliniert durchgeführt, ist das System zum Scheitern verurteilt.

- In den meisten heutigen Anwendungen von OKR werden die Quartals-OKR um zusätzliche Jahres-OKR erweitert, um nicht Gefahr zu laufen, in Aktionismus zu verfallen.

- Die Entlohnung wird in MbO gerne an die Ziele gekoppelt, mit zwei typischen Konsequenzen: 1. Es liegt meist im Interesse aller Beteiligten (mit Ausnahme der Inhaber) Ziele eher konservativ zu setzen, um sie leichter zu erreichen und Bonus zu kassieren. 2. Ziele werden zum Selbstzweck. Selbst wenn sie schlecht gesetzt wurden oder nicht mehr passend sind, werden sie trotzdem verfolgt, um den Bonus zu kassieren. Damit stehen sie der Agilität entgegen. Anders bei OKR: Die Entkoppelung von der Entlohnung ermöglicht es, Ziele ambitionierter zu formulieren, da das bestrafende Korrektiv der Zielverfehlung wegfällt. Da dies nicht bei allen Zielen sinnvoll ist, unterscheidet man bei OKR zwischen commited OKR, also solchen die zu 100% erreicht werden müssen, und aspirational OKR, bei denen man von einer durchschnittlichen Zielerreichung von 70% ausgeht.

- MbO-Ziele werden typischerweise von oben nach unten kaskadiert (also top-down). Der Manager leitet aus seinen Zielen dabei die Ziele für seine Untergebenen ab und gibt ihnen diese vor bzw. vereinbart sie mit ihnen. Auch bei OKR verläuft ein guter Teil des Prozesses top-down. Allerdings werden OKR nicht vorgegeben für die nächste Stufe, sondern der Mitarbeiter erarbeitet seine eigenen OKR als Beitrag zu den OKR der Einheit (Abteilung, Bereich, etc.). Insofern werden OKR auf jeder Stufe bottom-up erarbeitet und abgestimmt. Noch aus einem anderen Grund werden sie allerdings als bottom-up bezeichnet: Das Unternehmen kann auch zulassen, dass in einem gewissen Ausmaß (bis zu 50%) OKR auf unteren Ebenen generiert werden, ohne dass sie auf ein offensichtliches, höheres OKR einzahlen. Auf diese Weise kann ein OKR tatsächlich bottom-up nach oben wandern und OKR auf höherer Ebene nach sich ziehen. Das heißt auch: nicht jedes OKR hat notwendigerweise ein „parent“ oder „child“.

- Besondere Bedeutung hat bei OKR zudem die sideways Abstimmung, also das alignment. Damit ist gemeint, dass OKR auch horizontal mit anderen Einheiten abgestimmt werden. Voraussetzung dafür ist einer der massivsten Unterschiede zwischen MbO und OKR: OKR sind öffentlich und zwar über alle Ebenen hinweg. Und an diese Stelle passt auch eine bedeutsame Warnung: Transparenz in den Zielen bedingt eine Kultur, die geprägt ist von Offenheit, Verantwortungsübergabe, einem positiven Umgang mit Fehlern und gelebtem Feedback. Mangelt es an dieser Kultur, kann man in Anlehnung an ein Sprichwort sagen: „Culture eats OKR for breakfast“. Widerspricht die Kultur dem Ansatz von OKR, verliert OKR. Dann haben sie ein bürokratisches System, das wertlose Ziele verwaltet.

Sind nun OKR also das Wundermittel für fokus-lose Organisationen? Oder doch nur alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen?

- OKR sind das Wundermittel. Richtig eingeführt können Sie Ihre Organisation enorm pushen. Und Sie werden Ihrem alten System keine Träne nachweinen.

- OKR können allerdings schnell auch nur alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen sein, wenn sie bei der Einführung nicht sehr sehr viel Geduld und Sorgfalt walten lassen. Eine Organisation braucht eine Kultur, in der OKR funktionieren kann. Hat sie diese nicht, sollte zuerst die Kultur verändert werden, ehe OKR eingeführt wird. Der Widerstand gegen OKR kann sonst immens ein.

Schreiben Sie mir gerne Ihre Anmerkungen und Fragen rund um OKR. Ich sehe es als großes Privileg Unternehmen und Führungskräfte dabei zu unterstützen, OKR erfolgreich zu etablieren. Denn am Ende profitieren wir alle davon, wenn es noch mehr Unternehmen schaffen, Großes zu leisten für die Menschheit als Gesamtes, mindestens aber für ihre Mitarbeiter und Kunden.

Weiterführende Literatur:

Grove, Andrew (1983). High Output Management. Random House.

Doerr, John (2018). Measure What Matters: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs. Penguin Publishing Group.

- Veröffentlicht in Inspiring Leaders, OKR